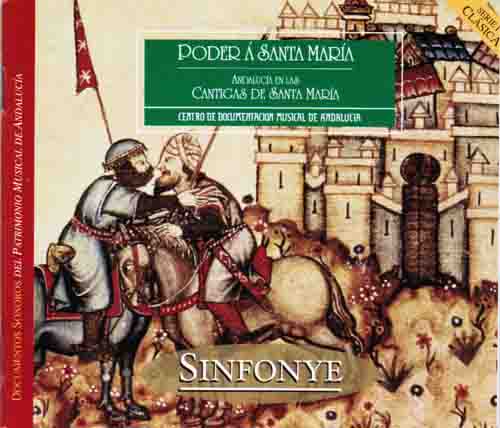

Poder á Santa MarÃa

Detail DS - 0110 You can buy this record here 11 € Poder á Santa MarÃa AndalucÃa en las Cantigas de Santa MarÃa

PODER Á SANTA MARÍA ANDALUCÍA EN LAS CANTIGAS DE SANTA MARÍA DEL REY ALFONSO X EL SABIO (1221-1284)

1. BEN GUARDA SANTA MARÍA (Cantiga 257). (A, B, D, e, F, g, H) 5’20" A VIRGEN MUI GRORIOSA (Cantiga 42). (D, F, H) 1'44"

2. PODER SANTA MARIA (Cantiga 185). (B, C, e, F, g, H) 10'21"

3. SANTA MARIA, VALED Al SENNOR (Cantiga 279). (A, B, e) 2'41" POR NOS VIRGEN MADRE (Cantiga 250). (A, B, e) 1'42" QUANTOS ME CREVEREN LOARAN (Cantiga 120). (A, B, e, H) 3' 16"

4. OS QUE A SANTA MARTA (Cantiga 344). (D, F, H) (instrumental) 3' 14" SEMPR'A VIRGEN GRORIOSA (Cantiga 345). (A, B, D, e, F, g, H) 9'42"

5. Improvisación Instrumental. (C, H) 3'20"

6. A QUE POR NOS SALVAR (Cantiga 169). (A, B, e, g. H) 6' 10"

7. O QUE MUI TARDE OU NUNCA (Cantiga 321). (B, C, e) 9’08"

8. ONTRE TOLDALAS VERTUDES (Cantiga 323). (A, B, C, e, F, g, H) 10’29"

Duración Toral: 67’07"

SINFONYE

EQUIDAD BARÉS: voz (A) VIVIEN ELLIS: voz (B) STEVIE WISHART: violín medieval (C), zanfona (D), voz (e) PAULA CHATEAUNEUF: oud (F), voz (g) JIM DENLEY: percusión (H) Dirección: STEVIE WISHART

|

About THE MUSIC AND PERFORMANCE OF THE CANTIGAS The melodies of Alfonso's Cantigas tend to be more predictable and forward moving in comparison to the cansos of the Troubadours. They are more reminiscent of the provençal dansas with easily memorable, short-ranging phrases which suggest strong metrical feels even short though the rhythm is often ambiguously notated in the Cantigas manuscripts. The musical form of the Cantigas a is remarkably consistent, usually with the second half of the stanza sharing the same melody as the refrain, as in the French virelai. In contrast to this lengthy miracle songs there also a handful of more concise Cantigas in rondeau form. With their internal and final refrain limes these Cantigas resemble French caroles, or dance-songs which h are documented as being performed with alternating solo and chorus singing and we have adopted this manner of performance in our sequence of Cantigas beginning Santa Maria, valed, ai sennor. The musical notation of monophonic repertories th communicates only the melody for the opening stanza pr and refrain and no other musical indications so the of modern-day performer must be guided by informed speculations and inevitably, by more subjective personal taste. The longer miracle songs follow the needs of the As singer and include instrumental improvisations to up the long successions of stanzas. We also Forms the refrains communally so that the soloist paused if desired -and this alternation of vocal ores further heightens the Cantigas structure with soloist holding the main attention when communicating the narrative and the repeating refrains moments of release- both for the performers and r audience. The incessant repetition of the refrains suggested the need to embellish the melody by improvising simple organum based harmonisations, and in the case of O que mui tarde ou nunca the melody invited canonic embellishment. The melodies of some Cantigas share many of the lame mal patterns and phrase structures and this common material suggested ways of linking particular Cantigas to one another and also ways of improvising accompaniments. The extended Cantiga Sempr'a Virgen Gloriosa is framed with and instrumental realisation of me a Santa Maria -their melodies are so similar that their various phrases are readily interchangeable and provide satisfying variations to one another. The stanzas of Ben guarda and A Virgen mui groriosa also have a similar melodic outline which led us to interpret the latter melody as an instrumental postlude. As one of the richest artistic centres of medieval Europe, Alfonso's court in Seville was renowned for its patronage of musicians from both the Arab and Christian cultures. The most complete Escorial manuscript (j.b.2) includes forty-one miniatures showing Christian, Jewish a Moorish minstrels playing a plethora of wind, string keyboard and percussion instruments. The second Escorial manuscript has a very different layout, with each Cant being illustrated in full and its musical scenes seem relate to contemporary performance practice in contrast to j.b.2 which seems more of a pictorial catalogue of dive instruments. In the first Cantiga of T.I.1., Alfonso explains his reasons for the collections and the accompaying illuminations shows him framed by scribes, singers and a waisted guitar (vihuela de penola). The illustration Cantiga 120, shows three figures linked in a circle dance behind Alfonso and his musicians which again supports its interpretation as a dance song. Our instruments are a mixture of mode reconstructions and traditional instruments which s resemble 13th century models. The medieval fiddle and sinfonye are based upon 13th and 14th century instruments. In the case of the oud (medieval lute) which was considered the king of Arabic instruments, the most conservative models extant today strongly resemble medieval depictions and it seems mi appropriate to use this traditional design rather than a reconstruction. This is also the case with percussion instruments such as the round frame drum which is depicted alongside a waisted fiddle in illustrations from a second Galician-Portuguese collection, the Cancionero de Ajuda. Square drums are likewise depicted in a number of thirteenth century Spanish carvings such as those in Burgos Cathedral and both desings can still be found today in Spain and Portugal, as well and in Arabic music. Our string instruments are strung entirely in gut or silk and adopt medieval tunings which indicate courses (double strings) on the fiddle as well as the lute.

Steve Wishart

INSTRUMENTS: -Medieval Fiddles: waisted fiddle by Alan Crumpler (Leominster) and oval fiddle by Bruno Guastaldi (Oxford). Tuned according to Jerome of Moravia's Tractatus de Musica. -Oud (Medieval Lute) by Saleem Elyass, Damascus. -Frame Drums: traditional hand-played drums from northern Spain (pandeiro) and Morocco (various sizes of bendir), after medieval representations. -Sinfonye (Hurdy-Gurdy), after 13th century Castilian representations and extant Galician instruments by Christopher Eaton (Upton-upon-Severn).

ANDALUCIA and the CANTIGAS DE SANTA MARIA

Alfonso X (d. 1284) is one of the European Kings of his time who with his enthusiasm for the arts and sciences enriched the cultural heritage of Europe. Proof of that is the consolidation of Castilian as the vernacular and the language of culture and the qualified use of Galician as a literary language, together with his work as legislator and historian. There was also important progress in translation, with the appearance of Castilian versions of Arabic, as well as Latin, works thus broadening the cultural wealth of the Iberian Peninsula and benefitting the rest of Europe in the process. Alfonso X's Marian song collection is one more example of this artistic energy. It consists of a repertoire of lyric pieces, most of them strong in narrative content, that the King (who was nicknamed `El Sabio' -the Wise-) composed and compiled throughout his life. Apart from the lyric nature of the texts, it is worth noting their great historic and sociological interest: they refer to known events corroborated by other documentation and, being set to music, they contribute to our knowledge of contemporary Hispanic social customes. It can be said that, in the century in which Dante Alighieri wrote The Divine Comedy the great monument of Mediaeval mentality, and in which theological rationalisation began with the Summa Theologiae of Thomas Aquinas, Alfonso X presents us with a form of humanism because, although the Cantigas de Santa María exalt the divine in the face of human uncertainty, humanity itself in all its weaknesses and its strengths is not excluded. Thus the text, and the miniatures which illustrate it do give us an impression of the reality of life in the l3th century.

Alfonso X and Andalusia If such is the case for Spain as a whole, even more can be learnt about Andalusia. Its geography and the fact that it was the frontier with the Moslim Kingdoms are mentioned in more than 70 texts. Alfonso proclaims himself king of Andalusia and all the other kingdoms therein: "Rei, e da Andaluzia dos mais reinos que y son". |